Awesome. Awful. Awe-Inspiring. Wonderful. Overwhelming. Reverence. These are big feelings straddling an underlying instinct to respect some things as incomprehensible or unknowable.

Just as I was about to write this post back in October my friend Kari shared her own, much more qualified thoughts. I urge readers wanting to know more from a psychologist’s perspective to take a look. Meanwhile I will focus more on my personal experience with awe and my understanding of it’s relationship with reverence.

Awe and reverence

Awe and reverence are not the same thing, but they are related. In practice we often experience them together. Awe opens the door for revereance. Awe is the emotional shock of scale, power, or complexity that exceeds our mental models. Reverence is what lingers afterward, shaping how we treat what we have encountered. Awe destabilises us, upsetting our perception of power, control or understanding. Reverence is a resultant, though not guaranteed, behaviour. Together, they form an ancient emotional pairing that played a key role in our evolution.

For most of the 300,000 years of human history, these instincts were not optional or abstract. Our ancestors were consistently exposed to forces vastly larger than themselves: weather, fire, animals, seasons and mass migrations. Awe would have been triggered often, and reverence would have functioned as a behavioural stabiliser, encouraging restraint, care, and respect in environments where overreach could be fatal. Groups that learned to treat certain places, animals, and practices as untouchable were the ones that endured. The mistakes of overextraction or exploitation are now stubs on the evolutionary tree. Long before the birth of formalised ethics and codified laws, awe and reverence helped align human behaviour with ecological reality.

Awe before language

My earliest personal memory of awe came before I had a word for it. I was perhaps 7 years old, on the verandah of my parents’ farm in South East Queensland. The drought that started before I was born had finally broken. Giant drops of rain fell hard and continuously for what could have been hours. I had only ever known the wide gully at the bottom of the hill as a vast, flat stretch of dirt with sparse patches of grass where sheltered by the feeding troughs. The water sheeting off the surrounding hillsides converged into a vast, swirling brown torrent, that completey submerged the valley floor. It was as much a flood of emotions as water.

Relief and excitement flowed alongside something else entirely: the sudden awareness of scale and the power of the elements to transform everything. My parents were verging on ecstatic. Dad found reasons to be in the water as soon as it had quietened and my little brother and I went with him. In a shallower gully eels brushed past our legs (where did they come from?) as dad held fast to our outstretched hands lest we get swept away. The rain was so welcome that the damage to the soil, fences, and risks to our lives seemed barely worth considering. What dominated was the sheer magnitude of change. The sense that the world could become so different, so quickly, and that it did not need permission.

That mixture of delight and overwhelm is important. Awe is not always fear. Sometimes it arrives bundled with gratitude or relief. It helps us recalibrate what matters, what we can change, and what we cannot.

Encounters that recalibrate scale

Years later, cycling through the centre of Australia as a young adult with my dad, awe returned in a very different form. One night, as we crouched in the dark over our tiny alcohol stove, the sparse bush around us suddenly lit up green. Looking up, I saw a vast meteor shower cascading spectacularly across the sky. Alone on the road, far from artificial light or human noise, I registered just how peculiar our regular existence is. How many such astonishing shows go completely unnoticed while we are shut in our homes, showering our eyeballs instead with pixels of artificial light?

The sense that thousands of generations before me had borne witness to such events was a powerful reminder of how short-lived our near-complete isolation from nature has been. Debris will continue blazing through the atmosphere and lighting the night sky well beyond the course of humanity. A similar sense of vastness in time and distance struck me while beyond the sight of land just last year. I couldn’t help but imagine dolphins frolicking about the bow of an early sailing vessel, some 3,000 years ago, and wondering if those ancient sailors felt the same way as me.

Other encounters of immensity brought awe without comfort. Perhaps closer to shock. Open-cut coal mines, seen from the sky stripped away any remaining delusions I may have had about human impacts on our environment. The great chasm, where once there was a mountain. The thousands of geological licorice stripes, each one representing millions of years. The expansive lakes of precious ground water, drawn up, contaminated, and left to evaporate. Footage of an atomic bomb test did something similar for me. It was not simply the destruction or death, but the realisation of what’s possible when angry apes find themselves wielding the power of gods.

When awe becomes moral vertigo

War museums in Southeast Asia in my early twenties intensified this discomfort. Carefully curated footage and towers of human skulls elicited a chemical response like I was chewing on copper. The systematic nature of the violence, the scale and the repeat of the same types of events across the course of “civilised” history dissolved any illusion that harm is accidental or rare. Awe in these spaces did not inspire admiration. It induced moral vertigo, a sense that human systems can and have amplifie cruelty just as effectively as community can and has amplified care.

Reverence in these moments was not about glorifying sacrifice or nationalism. It was about recognising the weight of consequence, and the thin line between coordination and catastrophe.

Birth, death and proximity

Some of the most powerful experiences of awe arrive not through scale, but through proximity. Theory became reality when I saw Adam’s head emerge, warm and wet, from my wife’s exhausted, but very alive body. This new life was no longer a hope for the future or a CT image. It was visceral. Vulnerable. Reverence followed without instruction, but by instinct. Life is precious and this was new life was mine to care for.

A lot of my work was in beef processing plants. When everything is working well the scale of death is difficult to discern, even while I have all the numbers in front of me. A broken conveyor on a site visit to the largest plant in Australia just last year, made it very real. In just minutes, great piles of meaty bones accumulated on the benches, in tubs on the stalled conveyors and on the floor. The killing already done, clearing the evidence now deferred to later. The scale of death, reminiscent of Cambodia, right here surrounding me on all sides made any further illusions of the innocence of meat impossible. It was a sobering experience, rooted in an undeniable awareness of cost.

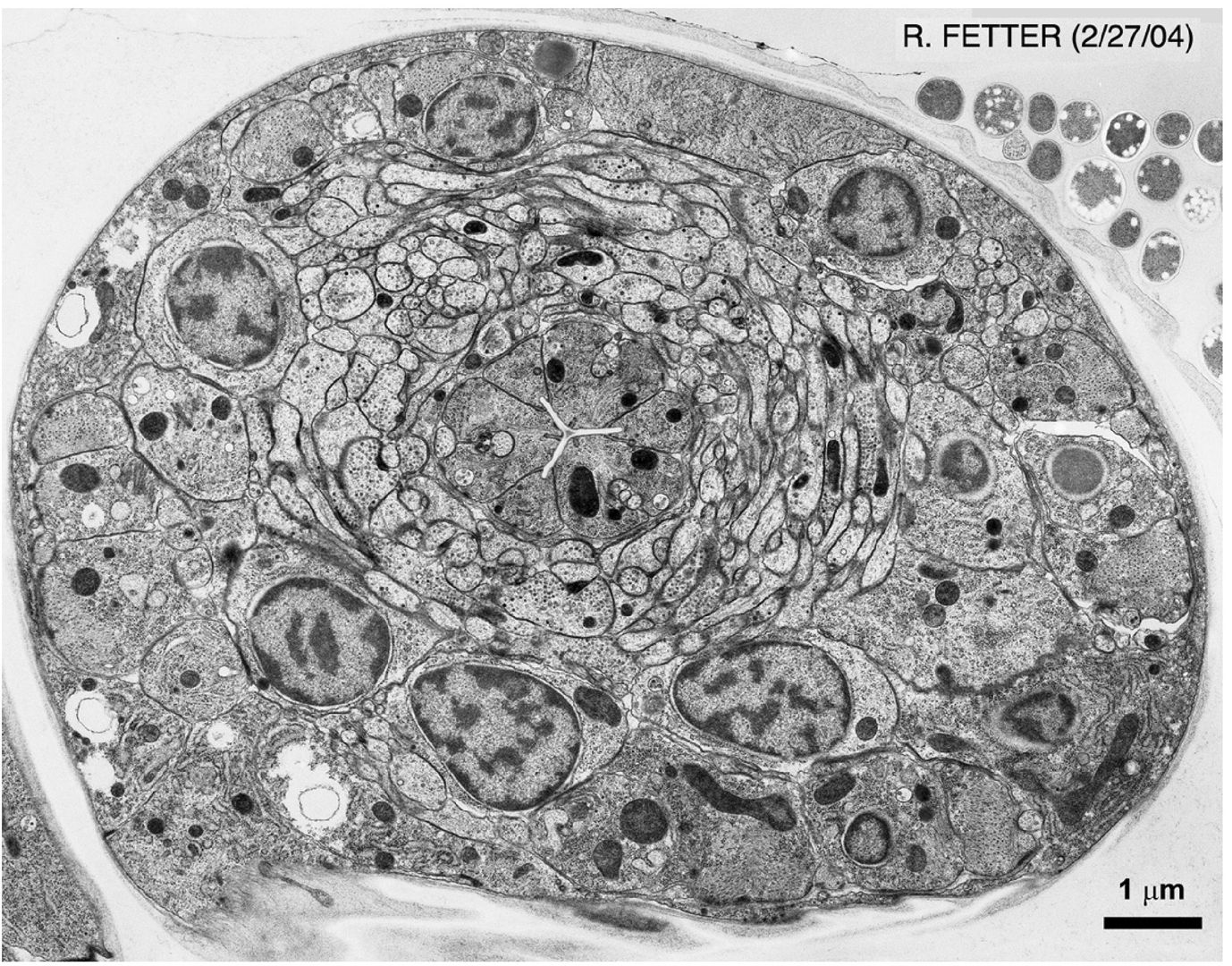

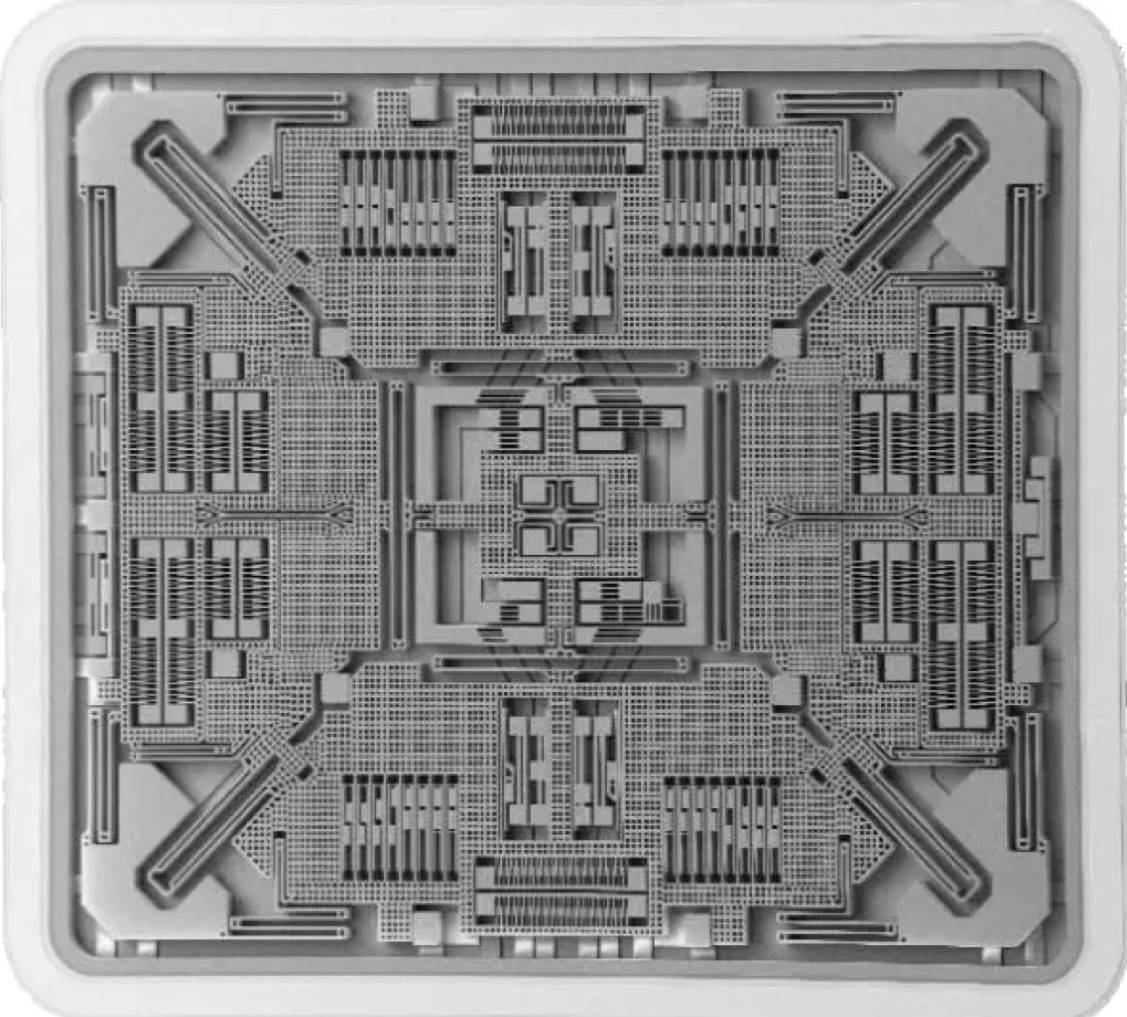

Cells, chips and whale poo

Awe is not limited to comparisons at large scale. Living cells next to the most complex man-made microstructures under intense magnification illuminated for me how incredibly far we have come in 250 years of modern science and how far we yet have to go to come near 10 billion years of evolution.

Some readers will be familiar with trophic cascades. A change to the top of a food web, that has major transformative implications for the rest of the ecosystem. The reintroduction of wolves into North American parks is a common example, with many complex changes including redirection of rivers. I recently learned of another, even more mind boggling cascade, starting with whale poo.

Whales feed at the bottom of the ocean where it is too dark for plants to grow and poop at the top, bringing nutrients with them into the brighter zone. This allows plankton to flourish, which as well as capturing a substantial amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide, also supports the rest of the food chain. The hunting of whales, which reduced their numbers by up to 90%, is likely to have played a significant role in reducing overal fish populations. The opposite of what might have been expected from simple observation.

The complexity is overwhelming. The time it required to arrive at this level of complexity and interdependence is beyond my comprehension. So awe arrives from both directions, reminding us that no single perspective is sufficient, and that confidence often collapses when we go closer or when we step back and see the whole forest.

This capacity to feel overwhelmed is not a flaw. It is a feature.

How culture redirected the instinct

Reverence for nature and our place in the universe has been under duress since the rise of civilisation. Early accumulators of wealth soon also accumulated power. They formed armies and built monuments at incredible scale. Gods were devised in likeness of the leaders and tales told that enforced the leaders rightful, godlike place in society. Revere your leader or perish. Revere your god or face eternal damnation.

One might get the impression that modern western culture has no place for reverence. Certainly religious reverence has dipped. It has supposedly been replaced with science, reason, rationality and data. In practice, however reverence has not disappeared at all. It has found new targets. We marvel at, worship and long-for great power and status. Billionaires, mansions, private jets and private islands. Followers, fans & favours. We are awestruck by sustained economic growth, by the latest piece of technology, tallest building, a space launch, record profits and unheard of productivity. These fascinations are rarely questioned at a foundational level, which is precisely how reverence operates.

The problem is not awe or reverence, but their misdirection. When these instincts are aimed at human-made systems, rather than the natural systems that sustain all life, any restraint that early reverence granted us is eroded. Instead extraction accelerates as we reward the extravagance with our attention.

Returning awe to a better place

Reasserting the natural role of awe and reverence does not require mysticism or a return to superstition. It does require awareness and exposure. Direct encounters with scale, with consequence and with interdependence, birth, death, and irreversibility. It requires fewer buffers between action and impact, and fewer stories that shrink or ignore reality to fit comfort or profits.

Our culture, insulated from the awe of nature and revering mostly things we have built on top of, is optimising itself into collapse. This is not planned or malicious as such, but a product of blindness, of ignorance and of misdirected hope, capitalised on by those with… ahem capital.

Why this matters for Living More with Less

To successfully Live More with Less requires recalibration. It requires visceral understanding of our position, as wee soft and squishy and slightly too-smart humans, in the world and the universe. Reverence for the world that provides for us, makes restraint of consumption feel rational and wholesome, rather than moralistic or sacrificial. Care feels critical rather than an optional nicety.

When we truly grasp the scale of our existence verse the impacts we are having, waste becomes repulsive. When we feel the consequences of our good choices in our hearts and our bad ones in our bowels, the right course of action becomes obvious. When we fully register the complexity, the interdependence and the fragility of life, living lightly and giving back is no longer some wild eccentricity, but the only sound path ahead.

Facts do not change minds, but feelings can, if we make space for them.

A better world will not emerge from better data alone. It will emerge when our oldest instincts are brought back to bear on what actually sustains us. Next we will look at status seeking.