Recently, I’ve been reading Our Tribal Future by Mike Samson (2023), a thought-provoking exploration into the hidden costs of loneliness and the profound benefits of human connection. Together with my recent interview with Gregg Easterbrook, who emphasized the mental health benefits of stepping away from social media and the news that’s designed to upset us, these insights reinforce something crucial: we are biologically hardwired to be social.

Evolution: Why We Became Social Beings

Humans evolved as profoundly social creatures. Our survival depended not on individual strength, but on our capacity to form and maintain groups. The “social brain hypothesis,” proposed by anthropologist Robin Dunbar, suggests our brains evolved to manage complex social relationships rather than environmental challenges alone. Indeed, Dunbar noted a direct correlation between primate brain size and group size, suggesting our cognitive evolution is closely tied to social complexity (Dunbar, 1998).

Biology: Socializing as a Physical Necessity

Our physiological need for connection extends deeply into our biology:

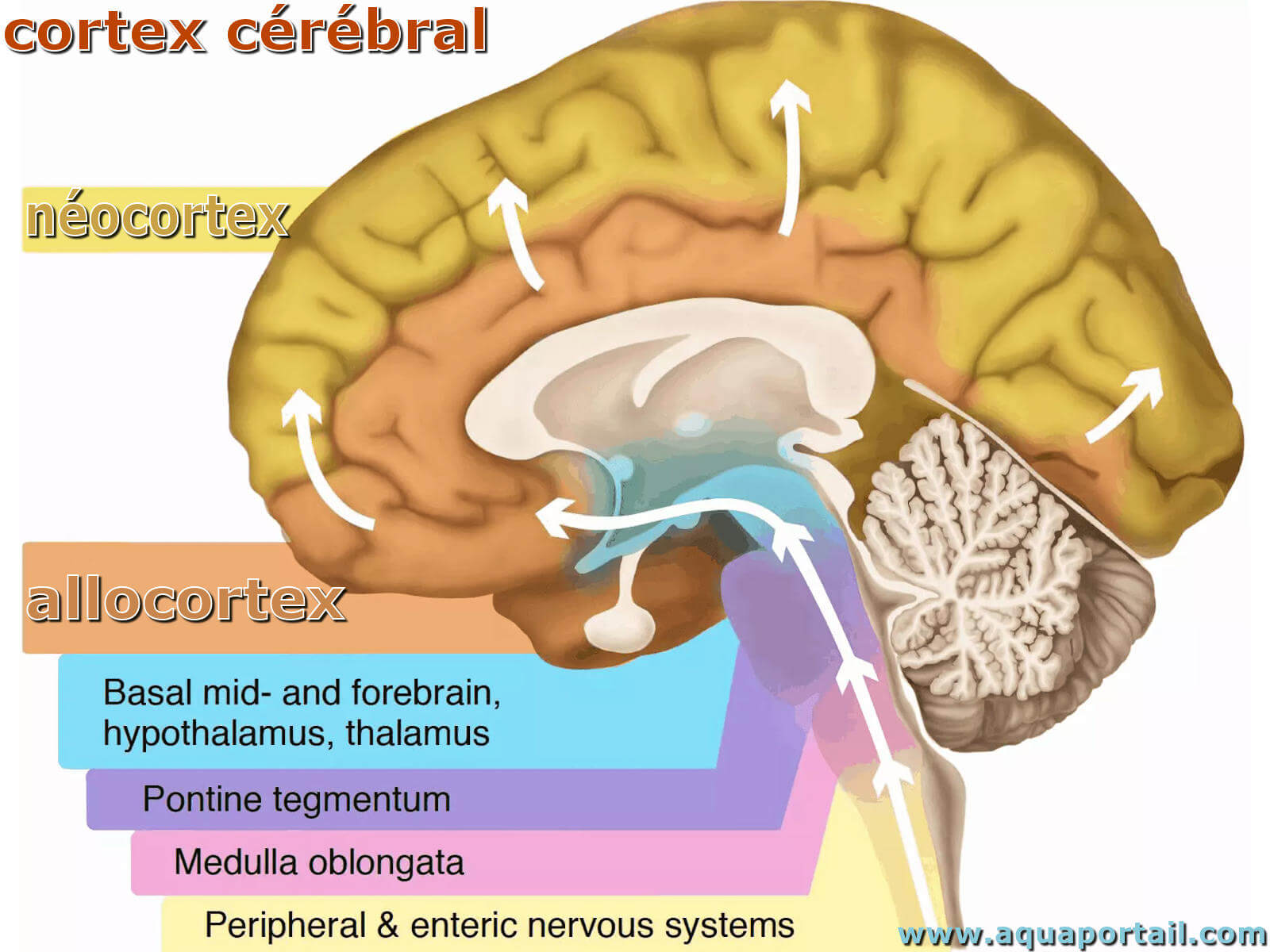

- Brain Structure: The vast proportion (80%) of our neocortex, responsible for higher cognitive functions, is involved in social cognition and interpersonal relationships. This illustrates just how biologically crucial our social life is, as growing and maintaining brain tissue is a energy intense and therefore risky process from an evolutionary sense. (Frith & Frith, 2012). The fact that so much of the “thinking” brain, which distinguishes modern humans from our early ancestors is devoted to social functions points to their importance in our evolution and ascension to the position of biological dominance we now find ourselves in.

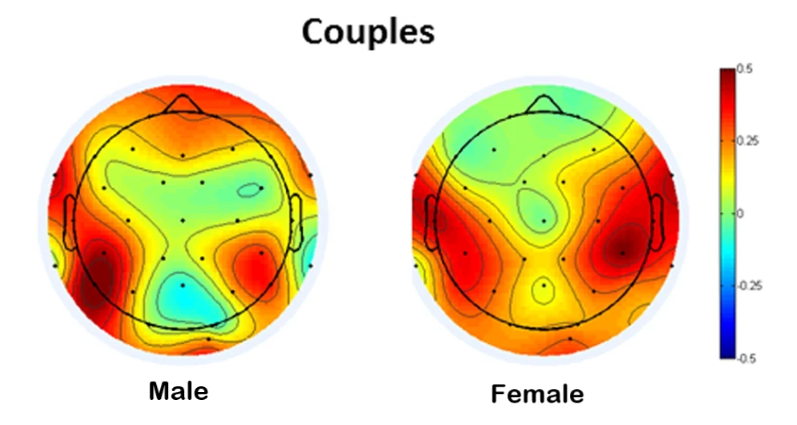

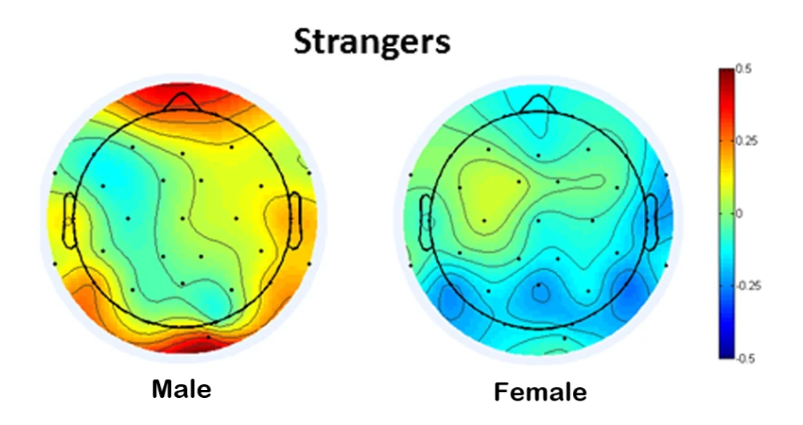

- Brain Wave Synchronization: Intriguing research has demonstrated that during meaningful social interactions, people’s brain waves can synchronize. This neural coupling enhances mutual understanding and empathy, promoting deeper emotional connections (Dikker et al., 2017). See image below for an example of this analysis.

- Chemistry: Regular social interactions decrease cortisol, our primary stress hormone, breaking the trigger pattern and reducing ongoing stress responses directly improving cardiovascular health, immune function, and mental health which are all otherwise negatively affected by elevated cortisol levels (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, 2018).

- Cardiovascular health: In a large-scale study published in Heart, researchers found people who maintained strong friendships and regular social activities had considerably lower blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and reduced inflammation resulting in a 29% lower risk of heart disease and 32% lower risk of stroke (Valtorta et al., 2016).

- Immune Function: Research conducted at Carnegie Mellon University found that people with richer social networks were significantly less susceptible to common illnesses, including colds and flus. Social connection appears to enhance immune response and support quicker recovery times (Cohen et al., 1997).

- Longevity: A landmark meta-analysis showed that social connection influences survival rates significantly in modern populations. Analysis of the data from over 300,000 participants found that people with stronger social relationships had a 50% increased likelihood of survival over an average follow-up period of seven and a half years compared to those with weaker social ties. The strength of this benefit is comparable to quitting smoking and moderating alchohol intake and even more significant than regular exercise and obesity (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010). A particularly interesting example of this, mentioned by Samson is the Roseto Effect, a tale of a close-knit community in the sixties USA with unusually low incidences of heart disease despite poor dietary and lifestyle factors.

- Preventing Cognitive Decline: Regular social interactions protect our cognitive health as we age, with one study revealing a 22% reduced incidence of dementia in a moderately socially isolated group compared with a highly isolated group. It is suspected this correlates with anxiety and depression which were associated with greater isolation (Kuiper et al., 2015; Jang et al., 2024).

Drag to see the difference (higher number / more red = higher correlation).

Psychology: Mental Health and Emotional Stability

Social interactions provide critical psychological benefits:

- Lower Depression and Anxiety: Research consistently links robust social networks to lower incidences of depression and anxiety. Close friendships are powerful predictors of happiness, emotional stability, and psychological resilience (Santini et al., 2020). Social interactions prove also to support a positive feedback loop, with less depressed individuals being more likely to perceive interactions positively and thus being more pleasant to interact with (Samson, 2023)

- Enhanced Emotional Intelligence: Regular, diverse social interactions enhance emotional intelligence, improving our ability to empathize, manage conflicts, and communicate effectively. Skills essential for maintaining mental wellbeing (Goleman, 1995).

- Combating Narcissism and Unrealistic Self-Expectations: In an age dominated by social media and so much focus on individual acheivements, more young people are naturally developing narcissistic behaviours than ever (Weidman et al., 2023). This is coupled with unrealistic standards driven by constant comparisons with the highest possible standard anywhere in the world thanks to prolific communication and algorithms designed to induce anxiety (More). Face-to-face social interactions provide essential reality checks, grounding individuals in authentic relationships and reducing vulnerability to self-obsession and feelings of inadequacy (Twenge & Campbell, 2018).

- Long-Term Happiness: Decades of research from the Gottman Institute affirm that meaningful relationships, built upon trust, communication, and regular interactions, directly correlate with higher happiness, reduced stress, and improved longevity. Their extensive longitudinal studies highlight that quality social relationships profoundly impact life satisfaction and overall health (Gottman & Silver, 2015).

Socializing as Essential Healthcare

Samson emphasizes that regular face-to-face social interaction isn’t merely pleasant, but should be considered essential healthcare, with as much emphasis given to improving social engagement as there has been in reducing smoking and promoting healthy diet and exercise. The evidence clearly indicates that prioritizing friendships, community involvement, and meaningful interactions is as powerful a strategy or moreso for health and longevity as the currently emphasised factors.

In short, cultivating regular and meaningful connections isn’t just good for your emotional wellbeing, it is profoundly beneficial for your physical health and longevity.

Modern Challenges to Socializing

While the evidence of benefits is clear, modern life brings unique challenges to maintaining meaningful social ties. Balancing work, parenting, and the instinctive aspirations of the hedonic treadmill (constantly chasing higher standards of comfort and success) often leaves little room for community and friendship. However, recognizing that these are obstacles and appreciating the immense value of local social connections can help us regain balance and live richer, more fulfilling lives.

Today’s generation of parents, in particular millennial fathers, are deeply invested in family life and parenting. Studies reveal millennial dads are spending more time with their children than previous generations, a positive shift that nurtures family bonds and childhood development (Parker & Livingston, 2019). Yet the time budget for this increased commitment often comes at the cost of broader social engagements, inadvertently shrinking the family’s social circle. And while the mums can often maintain friends through parenting years, due to the face to face mode of relating (as Samson puts it), dads have historically related shoulder-to-shoulder, I.E. engaged in a physical activity. The latter is somewhat less compatible with parenting, at least in the early years, and thus the number of close relationships in a young fathers life dwindle away, often never replaced.

Additionally, the pressures of social media, advertising that appeals to a scarcity mindset, a culture and economic models of individual performance, constant comparison and competition, combined with our natural aquisitive instincts encourage continual drive to work harder and work longer and maximise our yields. But with everyone doing this, there is a constant inflating of aspirations and expectations of personal success and material wealth as discussed in The Progress Paradox I recently reviewed.

With young people starting out in debt before finishing school or living week-to-week in later adolesence, to prove their independence, they are often not free of debt it again until nearing retirement age. Factored with economic uncertainty across all age groups, this is driving people to work, work, work, whether just to stay ahead, to get ahead of their peers, to meet their debt obligations or to feel financially secure, in case the future proves less abundant than the present. After the bombardment of our senses that is modern living and exhaustion from the extent of choices we have available, this constant striving naturally leaves little time and energy for genuine face-to-face community involvement, paradoxically reducing overall happiness and wellbeing.

Practical Benefits of Community Engagement

Local social interactions deliver numerous tangible benefits:

- Improved Romantic Relationships: Expanding beyond the nuclear family and maintaining friendships outside primary relationships provides significant psychological and practical benefits. Esther Perel highlights how couples who maintain diverse social connections enjoy greater relationship stability and satisfaction, as external friendships provide emotional support, fresh perspectives, and reduce relational pressures (Perel, 2006). Similarly, Samson emphasizes that external friendships enhance individual resilience and wellbeing, creating an invaluable emotional safety net and helping to bring out the best in both members of a nested couple (Samson, 2023).

- Community Resilience: Strong neighborhood ties greatly enhance community resilience in times of crisis, such as natural disasters, economic downturns, or personal hardships. Research after disasters like Hurricane Katrina or bushfires in Australia repeatedly demonstrates that well-connected communities recover faster and more effectively (Aldrich & Meyer, 2015).

- Efficiency and Shared Resources: Regular interactions foster sharing of resources, knowledge, and responsibilities, creating efficiencies such as shared childcare, carpooling, tool-sharing, or community gardening. Anyone need eggs or a cup of sugar?

- Improved Security and Convenience: Communities with stronger social ties report lower crime rates, greater collective vigilance, and increased overall neighborhood safety (Sampson et al., 1997).

- Cross-Age Friendships for Children: Engaging locally provides children opportunities to form friendships across age groups. Such interactions enhance empathy, social skills, especially the nurturing instinct, and emotional intelligence, fostering well-rounded development (Gray, 2013). I reviewed this book here with consideration to what a year out of school might mean for my children Adam and Dani.

- Shared Hobbies and Increased Accountability: Having friends nearby helps in making time for the activities we enjoy doing or feel we could be doing more of, whether that’s playing games, exercise, reading or fixing things!

Our Journey Towards Community

Despite understanding these benefits, reconnecting locally has felt challenging for me and Emelie. We have taken up a range of hobbies and special interests over the years and developed some important connections. Together with the friends we have held onto from school and work, we each have a handful of people we are reasonably close to, emotionally, however many are distant geographically and occupied with busy lifestyles as we all tend to be. Recognizing this isolation, we decided to make intentional, though initially awkward, efforts to engage with neighbours in our own street. This is something we have not actively done with a deliberate intent, beyond Trick or Treating, since our children were babies.

We are starting out with door-knocking and introducing ourselves. It feels very weird, scary and awkward. I’m afraid of rejection, of imposing on people or of creating conflict or animosity. Below is a brief video we took to share our feelings before setting out on our first “expedition” on the weekend.

Practical Ways to Start Building Local Connections

If you’re inspired to enhance your local connections, here are practical ways to begin:

- Introduce Yourself: Start simple. Say hello to neighbors, ask questions, and share small talk, relationships often grow from small interactions.

- Join Local Groups: Engage with existing local groups such as gardening clubs, Men’s shed, parenting groups, repair cafés, board game clubs, neighbourhood sports teams, or book clubs.

- Offer or Ask for Help: Small acts of sharing, like lending tools or volunteering skills. Asking for help is an incredibly powerful way to demonstrate vulnerability and build trust. Better if you can reciprocate at some point, but not essential to start out.

- Create Social Spaces: Host casual gatherings, like a backyard barbecue or afternoon tea to foster local interactions. We have tried this with Facebook events on the community page and have generally only attracted new arrivals to the neighbourhood from overseas. That’s been great too, but would like to cast a wider net to have a better chance of finding mutual interests. After doorknocking several more places we will invite some of the newly met people directly

- Participate in Local Events: Local school events, community markets, or volunteering opportunities such as bushcare and food banks are excellent platforms for connecting naturally.

Building these connections takes effort and vulnerability. It has become terribly scary to put ourselves out there, but the science is clear. The payoff in personal health and happiness, family resilience, and community strength is worth a little discomfort.

3 thoughts on “Wired for Connection – Why Humans Need Community”