“What difference can one person make anyway?“

This is a question I love to field, and this series will show that the answer is often “a lot”.

More Than a Job Title

I’m not one for small talk. When people ask me what I do, I know they usually expect a job title. While my work was always satisfying, I separated my identity from my professional occupation a long time ago. So instead, I talk about what matters to me. About Living More with Less.

By answering with values rather than a role, I know I’m changing the rules of the interaction. Still, I’ve found that this leads to more honest conversations, even if they begin a little awkwardly.

If the person seems interested, I talk about how lucky I am to have been born in Australia, in a time of unprecedented peace and prosperity [OWD]. How lucky I was to volunteer and cycle through Southeast Asia while still forming my sense of place in the world. And how those experiences set me and Emelie on the path of effective giving and sustainable living.

Over the past twenty years, while working part time, that path has allowed us to donate a substantial share of our income to highly effective charities. Statistically we have saved dozens of lives.

Now, at 41, those same choices have lead us to the unusual position of being able to step away from paid work altogether to focus our time on doing the most good we can.

The Reactions and the Reality

The responses I get when sharing this are usually a mix of barely concealed envy and obvious incredulity.

“You’re too young to retire!”

“Don’t the charities spend all your money on admin?”

“You must have been very well paid!”

The short answers are “no”, “no”, and “yes, at least by global standards.”

For more detailed answers, please take a look at the recently added FAQ page.

If the conversation allows, I also talk about the role our living choices play in reducing harm. I mention that if everyone lived like the average Australian, we would need around five Earths to sustain that lifestyle [Footprint Network]. I sometimes add that earning more than AUD 60,000 a year places someone among the wealthiest ten percent of people globally [GWWC].

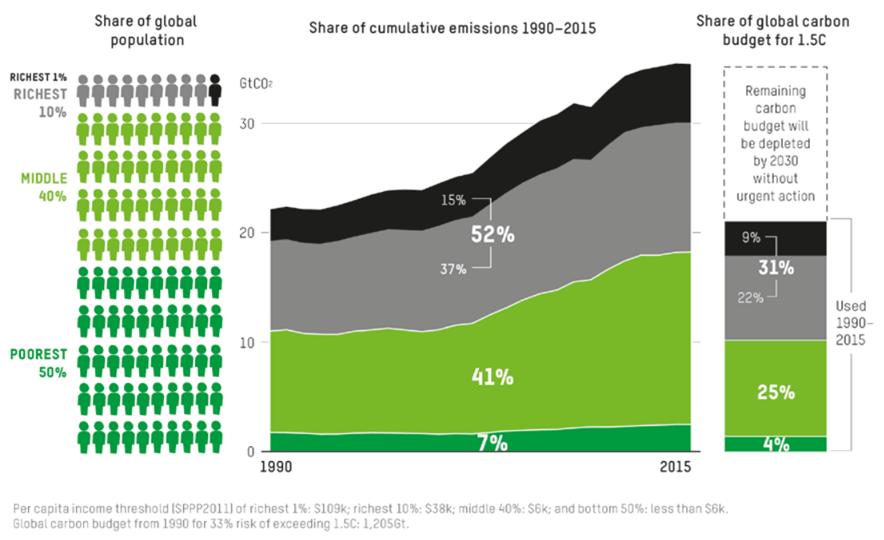

A major reason for the quality of life enjoyed by us, the richest ten percent, is the vast and accelerating use of energy and materials since the industrial revolution [UNEP]. Historically, our group is responsible for almost half of cumulative greenhouse gas emissions. This isn’t just a legacy of the past though, its embedded in the standard of living many of us have come to expect today and may imagine for our future.

The State of the World

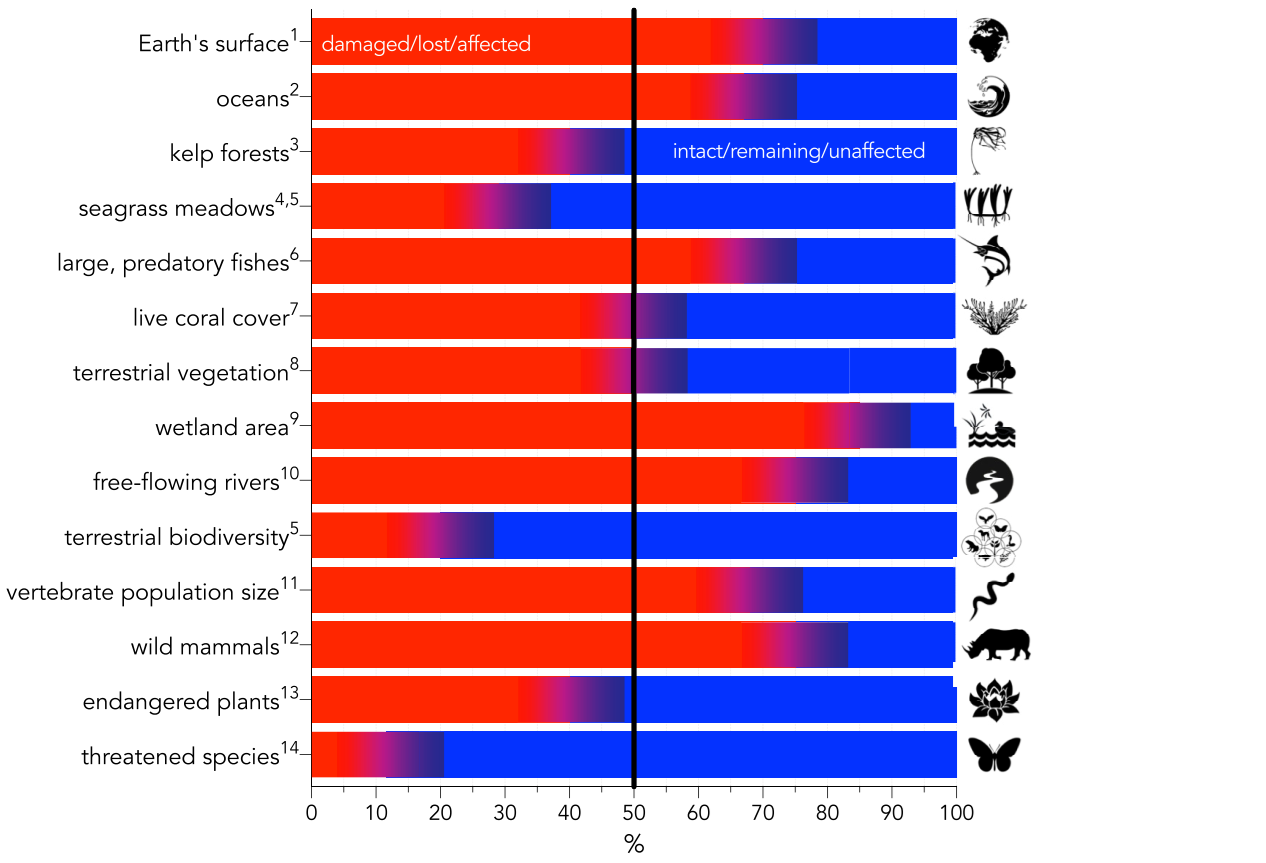

We have likely already passed the chance to limit global warming to 1.5°C, the goal agreed to in Paris in 2015 [UNEP]. Since COVID, the number of people living in extreme poverty has increased for the first time in modern history and is trending upwards [OWD]. Around 16,000 children still die every day, most from preventable causes [OWD]. Species are being driven extinct at many times the natural background rate [FCS]. The Doomsday Clock, which gauges the threat of nuclear annihilation sits closer to midnight than ever before [BAS].

This is a lot to take in. For some people, it feels hopeless.

People say:

“What difference can one person make?”

“We’re all stuffed so what’s the point of changing now?”

“There are too many people. If we save lives, doesn’t that just make things worse?”

“We have our own problems. They can deal with theirs.”

That last one hurts.

There is truth in it. Everyone faces real constraints, whether financial, emotional or cognitive. It is genuinely hard to care about distant suffering while managing your own life. And yet, the more we are able to extend care beyond ourselves, the more meaning our lives tend to assume.

Imagine you were born into extreme poverty. What would you hope for?

On population, the evidence is clear and consistent: saving children’s lives reduces population growth [GM]. When more children survive past early childhood, families reliably choose to have fewer births. This pattern holds true across every region, race and religion.

From Denial to Acceptance

As for doomerism, apathy, and overwhelm. I understand them. I’ve lived there.

Once you really take in the state of the world, there are a few broad directions you can go.

One option is to look away. For as long as we have working air-conditioning, plenty of coal, an effective border force, and comfortable bank balances, we can decide to enjoy what we have and assume the rest is someone else’s problem. This isn’t absurd; it’s psychological self-defence. I gave this path a go for a few years. But living with cognitive dissonance is challenging, in its own way. For me it gradually turned into anxiety and agitation. I knew something was out of alignment, even if I couldn’t name it at first.

The other option is to accept what we know to be true. This isn’t just an intellectual shift. It resembles grief. Anyone who has experienced significant loss will recognise the cycles of denial, anger, bargaining, sadness, and partial acceptance. It’s nonlinear and in my experience, it’s never really finished. But with it eventually comes relief, and the space for real, unbridled joy.

If you are stuck at denial, you are not alone and it’s not some personal failing. Vested interests have spent decades and billions of dollars encouraging disbelief and delay to protect their bottom line [IM].

For me, the grieving process felt like waking up after hosting an epic party.

Cleaning Up After the Party

The house is a mess. Some damage is permanent. I didn’t personally break everything, and some guests were invited long before I had a say. The garden is on fire, the roof now leaks, the front door is gone, and pretending otherwise won’t make it untrue.

I can’t undo the party. I can’t clean everything alone. But going back to bed won’t help either.

We can’t put the carbon genie back in the bottle. The emissions already released will influence the climate for centuries. Many ecosystems won’t recover in any meaningful human timeframe. Future lives saved don’t erase the grief of lives already lost. We are already living with more frequent floods, fires, droughts, and the social and financial stresses that come with them. My home insurance doubled in price twice in the last two years. And no, I don’t actually host wild parties!

As members of the wealthiest ten percent, we have been partying most of our lives, even if it doesn’t feel like it. And our financial position means we can, and should, do far more than our proportional share of the cleaning up. This brings us to the familiar debate about individual versus collective action, often framed as an either/or choice.

That framing itself is a mistake, as it puts either all or no accountability on the individual.

Individual Action, Collective Change

Collective action has been essential to every major social and environmental improvement of the past century. We need regulation, political pressure, and institutional change. No serious response to our predicament avoids that.

But while we continue to live in market economies, individual choices still matter. They express what we value, they shape demand, normalise alternatives, and build credibility for broader change. They also produce direct, measurable impacts.

Treating personal responsibility and systemic reform as mutually exclusive is another way of offloading responsibility. It’s like blaming the council for approving the party, or the manufacturer for selling the alcohol, while refusing to pick up a broom.

We should absolutely write to our representatives, challenge our banks, and pressure our employers. We should also start putting our own houses in order.

That is the core premise of the Living More with Less project, and it has been remiss of me to wait this long to document it. Better late than never.

What Difference: The Series

Over the coming months, I’ll share a series of posts showing the scale of impact one middle-class Australian can plausibly have through a combination of changes in consumption and effective giving. The specifics won’t apply to everyone, but the order of magnitude will be similar, and I expect most readers will find something useful.

I am looking at impacts across several areas, including personal health benefits, financial savings, benefits to society, reduced environmental impacts and improved welfare of others.

I’ve organised the series using the same key categories suggested in Make a Change. For ease of memory, I’ve used the four-letter curse words:

- Cows (diet)

- Cars (transport)

- Coal (stationary energy)

- Crap (goods and services)

- Cash (finance and charity)

- Call (collective action)

After some previous controversy on Reddit, where I was criticised for using commonly cited industry figures rather than official government statistics, I’ve taken extra care this time to make the claims as defensible as possible. That has meant slower writing and deeper research, but the trade-off feels worthwhile.

Making a Difference

To close, I’ll borrow a familiar story, adapted from The Star Thrower by Loren Eiseley.

An old man walking along a beach after a storm saw a young woman bending down, picking up starfish and throwing them back into the sea.

“Why are you doing that?” he asked.

“The tide is going out,” she said. “If I don’t throw them back, they’ll die.”

“But there are miles of beach,” he replied. “You can’t possibly make a difference.”She picked up another starfish, threw it into the water, and said, “It made a difference to that one.”

Every dollar we give to effective charities.

Every tonne of carbon we keep in the ground.

Every kilogram of poison we don’t release.

Makes a difference to someone, somewhere, sometime.