hedonism

Cambridge English Dictionary

noun

living and behaving in ways that mean you get as much pleasure out of life as possible, according to the belief that the most important thing in life is to enjoy yourself

Instincts, Pleasure, and the Role of Hedonism

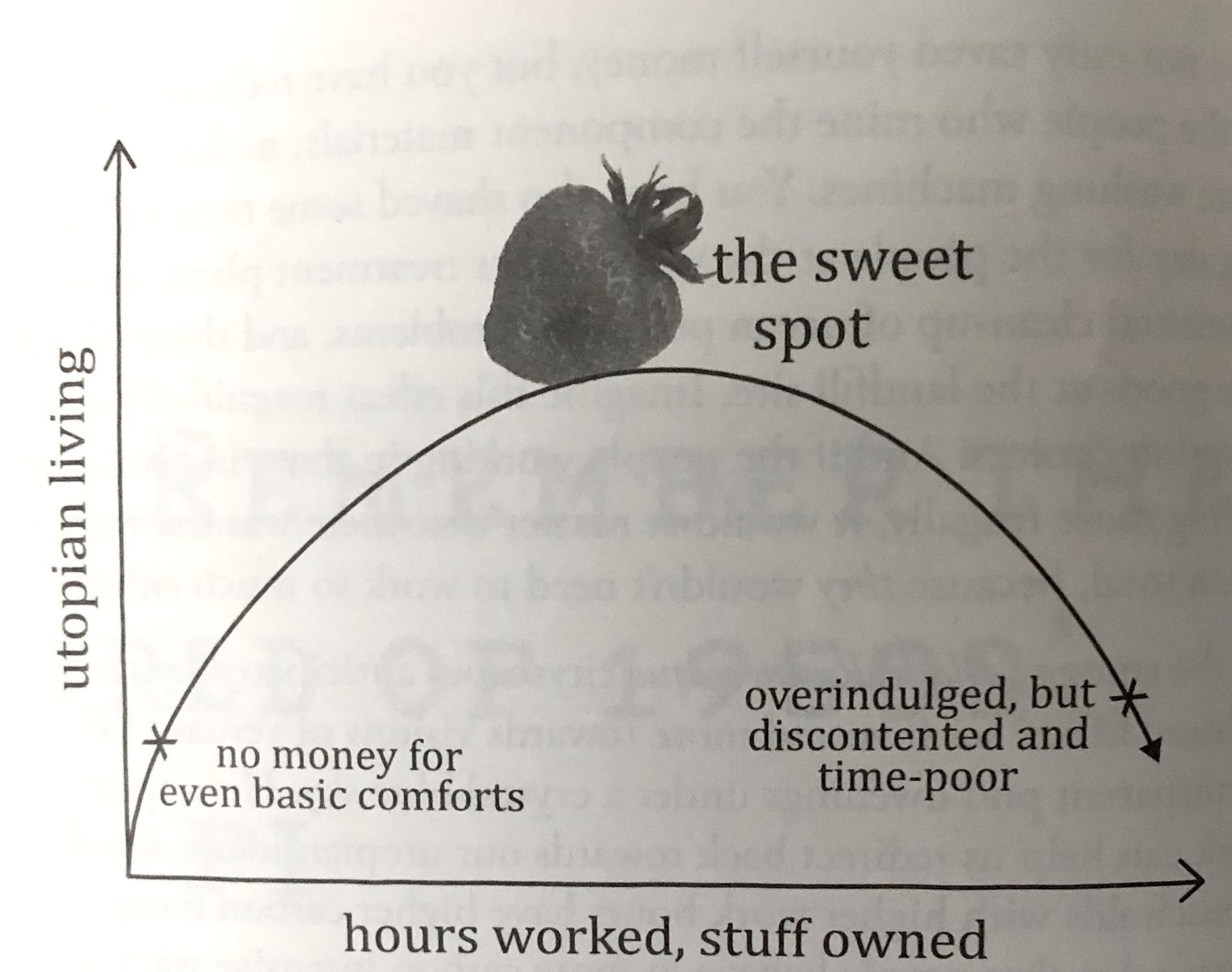

You might find it hard to reconcile the idea that hedonism and living with less really go together, but that’s what the living more is about in our project, and it’s just as important as the with less. If we just focused on the less, life would soon lose any sense of meaning, as what benefit could there be to improving or extending the life of others if not to experience pleasure. After all, we are animals and like all animals we are driven by our instincts.

And those instincts are simple: seek pleasure, avoid pain, survive. We do this by seeking food, shelter, warmth, comfort, and safety. We find mates and court them. And we store energy and food for future scarcity. These instincts have brought us to where we are, masters of our environment. But they’re also taking us somewhere dangerous. They’ve served us so well that we’ve outgrown their usefulness, at least in the way we continue to satisfy them.

We’re now at a point where continuing to follow these instincts blindly is undermining the very future of life on Earth, or at least of intelligent, conscious life. We do our best to overpower some of our instincts and have done so throughout the history of civilisation. We use reason, or lay additional conditioned responses over them, or trick them with substitutions of the real need. And to some extent, we must continue to do this. Many of our instincts have already been hijacked to keep us angry, tired, busy and consuming. It’s just business, after all.

But we needn’t ignore all of them. In fact, if we do, what’s left?

Frugal Hedonism and Reclaiming Joy

So instead let’s consider which instincts cause the least harm and bring us the most joy. Which cravings can still be met, but in simpler, lighter ways?

This is the heart of The Art of Frugal Hedonism by Australians Annie Raser-Rowland and Adam Grubb. It’s a collection of 51 short and often witty chapters on how to spend less money and enjoy life more. It’s as accessible as it is amusing. A practical guide to simple satisfying living without the martyrdom.

You’ll find tips on recalibrating your senses, on repairing or making do and a reminder of how well that serves to replace other dopamine seeking activities. There are reminders on the importance of play, along similar lines to previously discussed. They also include reflections on how to notice what you actually enjoy spending money on, when you do spend it. There’s wisdom on grime and resilience, on the value in needing other people and on the value of delighting in the little moments. Not just a memo of mindfulness, but a collection of useful and inspiring points that you can try on for size and leave on the shelf if they don’t fit. Even the chapter titles are curious—like “Be Materialistic,” which reminds us that materialism itself isn’t the problem. In fact, fully appreciating the things we already have might be the best way to reduce consumption.

Community, Connection, and Why Asking for Help is a Good Thing

One of my favourite chapters is 31: Have a Fine Ol’ Peasant Time. It celebrates the sense of satisfaction that can come from simple, hands-on activities, especially when done with others, reflecting the importance of social connections. Things like making jam or pickles, gardening, baking bread, or fixing things, when done alone, can feel like real chores and hardly worth doing. Yet done with others, they feel far more natural and worthwhile and lend themselves to strengthening relationships.

That has been exactly my experience over the years working alongside Emelie on our own projects, as well as helping out in my local neighbourhood with small repair tasks, lending tools or a some muscle. It was very evident at the local Repair Café when I visited. It is, afterall a community built on this principle. And it wasn’t just among the volunteers, but with the regulars who come in with toasters or trousers or teapots and return with stories and gratitude.

Even just this week I had the opportunity to help a recently met neighbour sawing a tricky piece of timber. Then, later, accepting an old tube of silicone so I could finish replacing the glass in my bathroom window. As it turns out asking for help is one of the most effective ways of building trust and usually results in all parties feeling happier. So it’s not just about saving a few dollars. It feels great to be useful, not for a boss or a deadline, but for the people right there with you.

Altruism as Instinct and Pathway to Meaning

That sort of usefulness feels good. It’s a different kind of productivity. One that builds connection and meaning instead of bitterness and burnout. It is the call of the altruism instinct. Easily as important to the survival and flourishing of early humans as our self-preservation instincts, it is one we could once again nourish for the benefit of everyone. By donating to an effective charity and pledging to do so on an ongoing basis you can feed your own altruism instinct and feel even better than if you indulged yourself.

There are real pleasures we’re chasing here. Not the kind sold to us in ads, but the kind you find when you make that donation, or when you pick up a shovel, share a pot of tea, patch something with care or even just lay a minute longer in a warm bed with someone you love. When we slow down, we notice that the richest pleasures are often the most modest.

Ancient Voices on the Middle Path

The idea that we can be hedonistic without being lavish is not a new idea. Epicurus in 270BC, though noted to be fond of cheese and perhaps sometimes misrepresented as a champion of drunkards, was perhaps the first true frugal hedonist. He suggested that the key to pleasure was not indulgence, but understanding which pleasures are truly worth pursuing. For him, a simple meal shared with friends and accompanied by rich conversation could be the height of happiness.

The Buddha, too, sought to overcome the suffering that comes from worldly attachment, but didn’t deny the value of joy. His concept of the middle way speaks to this balance: neither overindulgence nor deprivation, but a life grounded in awareness, contentment, and compassion.

What are We Actually Giving Up?

These principles still apply. But in today’s world, the bar for what may be considered an ascetic or deprived living has been raised so high as to be comparable to that of nobles and royalty of past eras. The discomfort we may face by scaling back our lives is mild. A slight inconvenience or delay in gratification. Nothing like the lives of saints and monks, nor even their contemporary merchants or landholders. And if the reward for giving up a little of our convenience is actually more joy, more meaning, more time, more connection then maybe that’s a trade worth making.

Living more with less isn’t about going without. It’s about finding the things that make life worth living, about bringing those things into focus, and letting go of the rest.

2 thoughts on “Frugal Hedonism”