When we first started examining what a “one planet” lifestyle might actually require, I expected the numbers to push us beyond the margins of modern life, if achievable at all. The assumption is common: that living within planetary boundaries is practically impossible, and at the very least means stepping away from comfort, convenience and participation in mainstream society. Some of that is true, but that does not make it all bad.

Our personal experience agrees with research showing that a decent life is possible for all. Yes, we are closer to the margins, but we still live well. Research on Decent Living Standards by scholars such as Jason Hickel shows that providing everyone with housing, mobility, nutrition, health care and education requires far less energy and material throughput than wealthy societies currently use. The gap between what is sufficient and what is typical among high-income households is often much larger than the gap between sufficiency and planetary limits.

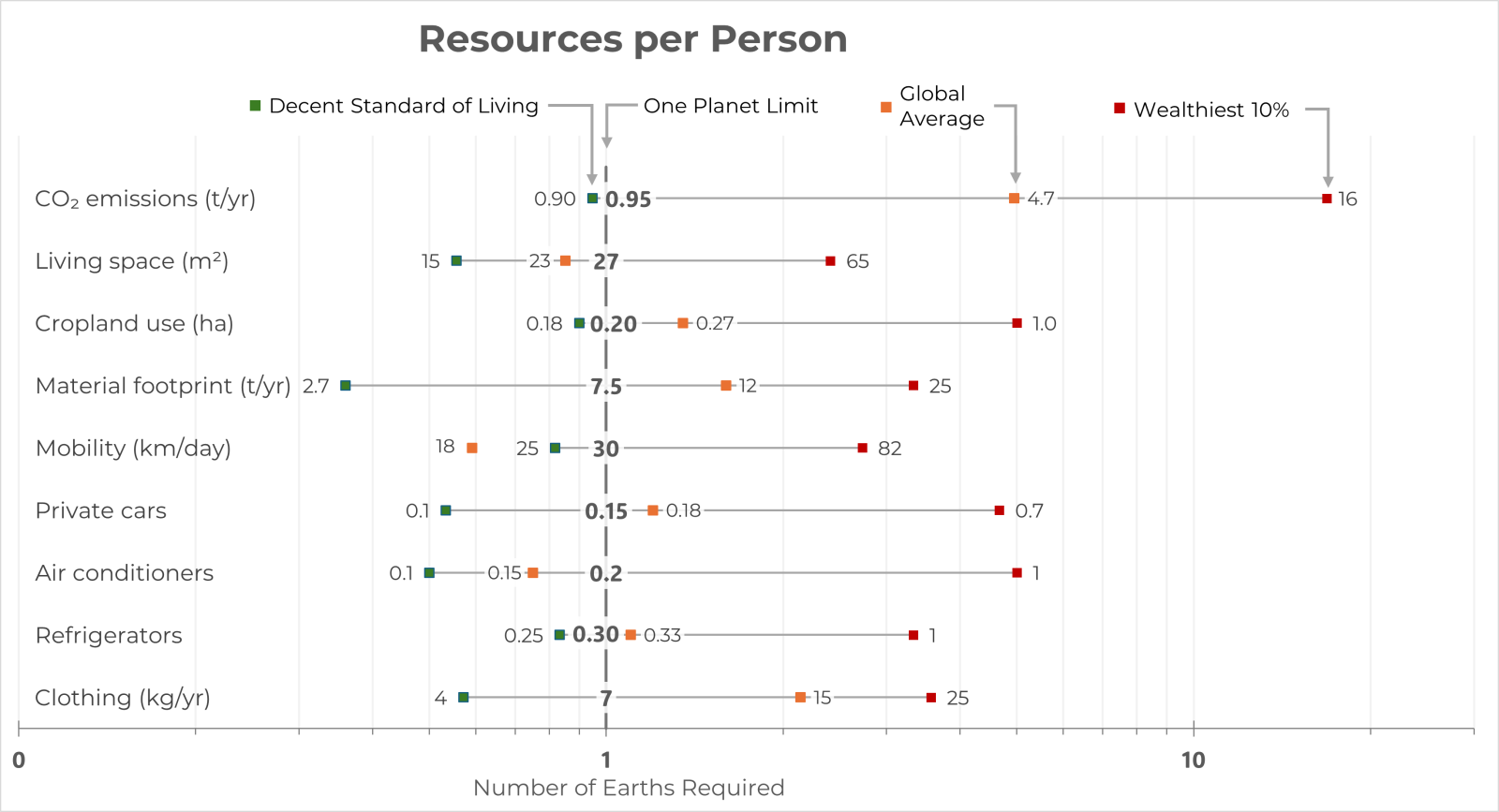

The table above illustrates this. In all cases the resources required for a decent life, as assessed in Hickel’s paper is below the the planetary-boundary compatible level, which I have labelled the “one planet limit”. Some are quite close. The real outlier is not adequacy though, but affluence, as shown for the wealthiest 10 percent.

What follows is not a claim of perfection. We live within public systems, use shared infrastructure and pay taxes and fees that fund materially intensive services. But by making a series of structural choices about housing, mobility, food and consumption, we have found that a one planet lifestyle is not an abstract ideal. It is something that can be approximated within a fairly comfortable Western context.

Housing, Space and the Weight of Concrete

Living space is one of the clearest examples. The planetary-compatible level in the table is 27 square metres per person. For a family of four, that equals 108 square metres. We live in a 90 square metre older home, located in a public transport and cycling corridor. By contemporary Australian standards it is modest. By planetary standards it is entirely reasonable. Living smaller has come with myriad other benefits as I wrote about previously.

The wealthiest 10 percent average 65 square metres per person. That scale difference translates directly into more concrete, steel, insulation, glazing and energy demand. Most of the material footprint of modern life is not in small consumer goods but in the built environment. Buildings, roads and infrastructure dominate the tonnage and the impact.

Building small reduces that demand. Avoiding new construction and renovations reduces it further. Converting and renting out our shed as a tiny living space means one less separate dwelling needing to be built. Given the material intensity of housing, that decision likely outweighs many smaller lifestyle adjustments, though we don’t buy anything new that we could reasonably get second hand.

We have also invested in home energy efficiency, have solar PV exporting more than we consume and purchase GreenPower. We do own three air conditioners for four people from a time we were trying to “fit-in”, but they were used for only perhaps 10 hours over summer. Mostly we rely on fans and accept some seasonal variation as a reminder we are alive and warming the planet.

Food, Land and Upstream Impacts

Cropland use in the table highlights the role of diet. A planetary-compatible level is 0.20 hectares (2000 square metres) per person. The wealthiest 10 percent approach 1 hectare. Much of this difference stems from animal agriculture, which requires vast land areas for grazing and for growing feed crops, relative to the dietary energy it provides..

Our freegan diet reduces land demand and fertiliser use. Since starting dumpster diving in November and sharing the excess we have driven our food impacts into negative territory, though see this only as possible on a small scale while there is an abundance of waste. It is also not necessary to remain within planetary boundaries, for those who might remark this is definitely a “fringe” activity. Growing some of our own salads to eat fresh and fruits, nuts and legumes for storage via drying, canning and pickling helps us rely less on refrigeration and high-input supply chains.

Our one small fridge-freezer works because our food system at home is structured to minimise waste. We use a lot of shelf stable dried goods, including rice and legumes and preserve excess fresh food to make it shelf stable. These are not extreme measures. Historically they were ordinary practices that reduce ongoing energy and material demand.

The key insight is that food impacts are largely upstream. Land clearing for grazing, ruminent methane, fertiliser production, farm machinery, transport and processing carry much of the footprint. Shifting diet and reducing waste address those heavy inputs more effectively than obsessing over minor packaging differences and food miles.

Mobility, Proximity and Design

Mobility is often seen as the hardest area to change. The planetary-compatible level in the table is 30 kilometres per day, which includes all forms of mechanised travel. The wealthiest 10 percent average 82km. That difference reflects not only personal preference but settlement patterns and infrastructure that have built in car dependence.

We bought our house close to public transport then changed jobs and chose schools to stay within comfortable cycling distance. In 2025 we drove about 1,000 kilometres in total. We rely primarily on cycling, public transport and ride sharing, and we are considering getting rid of our car completely, saving the almost $3000 it costs us just to sit there. We have also stopped flying. Recently, we hitch-hiked for practically zero impact travel.

These choices are easier because of location. Living in a transport corridor makes low car use feasible. If we lived far from services, it would be a lot harder to achieve. Systemic change is necessary to reduce car dependence. For a stable planet, cars will need to be pooled with one car for every two to four households.

Our taxes fund pensions, schools, hospitals and infrastructure. We still pay for medical services and school and sports fees. Those services carry embedded emissions and materials. Living in a wealthy country means inheriting that footprint. Even so, when we compare our lifestyle to the wealthiest 10 percent column in the table, of which we are a part, we come well under.

Bringing it all together

All together, smaller housing, choosing proximity, low car use, plant-based food and minimal new purchases bring our household closer to the levels that research suggests are compatible with both a decent life and planetary boundaries.

Choosing a one planet lifestyle has also meant saving tens of thousands of dollars each year, allowing us to give generously to effective charities and retire in our early forties. Perhaps it seems like a lot of sacrifice or inconvenience, but a lot of that comes down to framing. We are happy and fulfilled, in touch with nature, our senses and our community.

References for Further Review

Core planetary boundaries framework

- Tian, P., Zhong, H., Chen, X. et al. (2024) Keeping the global consumption within the planetary boundaries. Nature 635, 625–630 . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08154-w

- Richardson et al. (2023) Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Science Advances.

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adh2458

Per-capita and inequality analysis

- Hickel et al. (2024) How much growth is required to achieve good lives for all? Insights from needs-based analysis, World Development Perspectives, Volume 35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2024.100612

- O’Neill et al. (2018). A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nature Sustainability.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-018-0021-4 - Wiedmann et al. (2020). Scientists’ warning on affluence. Nature Communications.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-16941-y